A Clark Christmas 1954

by Marguerite Fetcher

This article originally appeared in theWinter 2025-26 issue of Art with Altitude.

It was Thanksgiving afternoon, a Currier and Ives kind of day. Snow sifted down onto an already deep pack. Houses were fragrant with turkey roasting for the evening meal. Cattle stood immobile in the snow, as close to the barns as fences allowed. Only the children were restless and at loose ends—pesky and obstreperous.

Each year previously, the men had cut Christmas trees on our upper ranch before the snow closed the roads. But not this year. It seemed such a simple thing to me to cut a small pine. I had watched Stanton do it many times with a few well-directed blows. So, full of nostalgia, I gathered the children—from our house, from brother John’s, and from the foreman’s—to go out and cut our own Christmas tree. A Thanksgiving the children would always remember, the start of a beautiful Christmas tradition!

I phoned the barn. Yes, we could take the little jump sled and one of the men would harness the team. The children came more or less enthusiastically—the enthusiasm seemed to be mostly their mothers’.

So, tra-la-la, we were off. The graceful cutter of old prints was replaced by a team of ponderous Percherons; and those happy, singing children? They had brought all the discontents of the earlier afternoon with them. No, they didn’t want to sing. No, they didn’t know any songs. And how come I sang off-key? Their desultory bickering should have been drowned out by jingling bells, but these had all been “lost,” because the foreman “didn’t hold with them city notions.”

I hadn’t had time to get truly annoyed with my load of brats before the team stopped dead. No amount of gee-yupping, chirping, or clucking would budge them. In books, this is the moment when some great danger appears, the horse’s sixth sense and stubbornness having saved everyone’s life. Not this time. There was nothing in sight. They had simply picked up a sound: their master’s voice calling from the barn. He wanted them back, so back they went. Would we mind taking a sick calf up the hill to Frank? The trussed-up calf was dumped in our midst. A scared calf—therefore, a calf with no control of bodily functions—was not in my nostalgic picture. But we graciously made this concession to reality.

Over the hill and through the woods we went, picking out huge trees to fell on our way back. All now very jolly. After delivering our calf—happy riddance—we pressed on into new, drifted snow, with no tracks to guide us. I just hoped we were still on the road, cut into the side of the steep hill. If we were off the road, we would indeed be off—and down the side of the hill. A problem I had not anticipated was turning around on this invisible one-way track. We could go a couple of chilly miles farther to the meadow—or try turning in a slight widening.

I chose the latter and made the children get out in case we did go over the edge. Then began the backward-forward maneuver, a foot gained each time. Again, a great geeing-and-hawing, great resistance from the horses who didn’t know me, didn’t trust me, and loathed going backward at any time. Understandably! The sled runners dug into the snow on each backward thrust, and in pulling forward the horses dug into belly-deep drifts. Slowly, we made it.

Now to select the six most beautiful trees. We were pretty choosy, considering every angle and branch as well as height—and very naïve. I stepped off into deep, deep snow on the downside of the hill, realizing as I approached a tree that its base—where a proper Christmas tree should be cut—was probably a foot or more below my feet, beneath the compacted snow. Walking? I was swimming slowly through four feet of drift. Chopping through snow to ground level might not have been difficult in itself, but I reckoned without branches. At four feet, the bottom branches were frozen together into a prickly wall well away from the trunk. There was no parting them to get in and under. I had to hack my way through. Once inside, surrounded by branches, there was no room to swing an axe. I had to peck. It didn’t take me long to realize I’d better tackle a smaller tree.

The children were happily making snow angels, but stopped to complain when I moved to a smaller tree. The problems were the same, but slightly less, so I soon decided that a tree on the upper side of the road would surely be easier. It was not. More howls from the young as I chose one that seemed perfect. Today I would call it a poor, spindly thing with weak branches—but that afternoon it was my prize.

Evelyn interrupted my work to whisper those dread words, the bane of every parent away from home:

“Aunt Peggy, I have to go to the bathroom.”

“Can’t you wait?”

“No.”

“All right, but it’s going to be awfully cold undressing in the snow.”

“Well, maybe I can wait.”

A few more pecks at my tree.

“Aunt Peggy, I have to go now!”

“Are you sure you can’t wait?”

Then suddenly, in frantic chorus: “Peggy, Aunt Peggy, the horses are gone!”

Horses that don’t stay put when the reins are dropped are committing one of the cardinal sins of ranchdom. One is allowed to be as profane or crude as one knows how on the rare occasions this happens. But sending them to eternal damnation via my vocabulary was of no help to me then—a mile from home, with small children (one of them very wet) and deep snow. We had better start walking, as the horses might stand behind the barn unnoticed for an hour.

Fortunately, our oldest son, Fred, saw them coming down out of the woods. He gave them the proper verbal lashing, turned them around, and drove them back to our rescue. No messenger from heaven was ever more happily received. And besides, this messenger wielded a mean axe—he had six good trees cut and on the sled in no time.

Nor were our tree problems over once we brought them down. The foreman put his tree up that very afternoon with lights and lavish trim. Of course, this started the refrain: “But why can’t we?”

My two answers were crisp. First, because we have to make decorations. Second, because we can’t possibly put the tree up until your father comes home.

While Stanton’s contribution to Christmas was getting himself and the animals safely home, we were deep in making ornaments, to the ongoing refrain: “But why can’t we put it up now?” Nothing modern like tin cans or plastic—no indeed, we were Currier-and-Ives-ing again.

Stringing cranberries was a disaster. The children had no interest, probably because they didn’t taste good. The younger ones had trouble getting the needle through the berries but no trouble getting it into their fingers. Blood, sweat, and tears!

“Dave! Take that cranberry out of your nose this instant!”

“For heaven’s sake, Linc, you don’t have to copy Dave. Stop it!”

Meanwhile the older boys discovered the berries made splendid slingshot ammunition. Had we wanted red polka-dotted walls, we could have had them easily enough. The popcorn was a moderate success—they strung a little and ate a lot.

Cookies as ornaments were a better project—depending on your perspective. Not from Billy’s, who got caught in the mixer and tore his shirt, nor from Linc’s, who burned himself. But decoratively, they were glorious. The children quickly used up the expensive trimmings I had bought, sprinkling them with lavish, wasteful hands. Then they turned to more original trim. My favorites were cookies decorated with paper clips, multicolored rubber bands, buttons, nuts and bolts, and large black rubber washers. True, they smelled funny baking, but who cared?

“Don’t you want one, Mother?”

“No thank you, dear, it might spoil my appetite.”

Best of all was baking a gingerbread house. I thought we would start while the youngest napped. No such luck—every child on the ranch was underfoot to lick bowls, stir, and taste. Whoever said, “Many hands make light work,” was crazy! They were all incipient, opinionated architects; a gingerbread city would not have accommodated all their ideas. We kept running downstairs for another box of gingerbread mix. Gingerbread for the porch, for a shed for the 4-H calf, for a garage that wasn’t in the directions. Little cars, dolls, and trucks all had to be accommodated. The popcorn we didn’t string became snowdrifts; grubby candy came out of pockets for trimming, and of course was retrieved the next time the donor got hungry. They loved it. Of course, it got dirtier as toy trucks ran over sugar roads, plainer as hungry boys ate the trim, and smaller as accidents befell. It was a true ghost town, like so many in Colorado, and pretty dilapidated by Christmas.

Stanton did get home in time to send letters to Santa. It’s the sending that’s difficult; the writing is the same everywhere:

“Yes, dear, you spell it C-L-A-U-S.”

“Dave, try to write neatly.”

“Of course Santa knows where you are.”

“You spell it PO-GO stick, but are you sure that’s what you want?”

Why do children in the city want horses, and in the country, miles from a sidewalk, they want roller skates? With gentle parental guidance, that Pogo stick Santa wasn’t bringing turned into skis hidden upstairs.

Letters were written on onion-skin paper, and if the fire was just right, the hot air carried them up the chimney. Ideally, they burned on the way up, disappearing from sight. But sometimes they fell intact in the front yard, where a worried child always found them. Worse still were the rare occasions when the letter didn’t rise at all, but caught fire and burned. This plunged us into odd explanations of thought transference to Santa, even metaphysics at a six-year-old level, and usually left us with a skeptical child.

Our real letters had gone out long since—addressed to Sears Roebuck, Gokeys, Marshall Field’s, and L.L. Bean.

Christmas Eve Day was dedicated to the animals; other work was put aside. Machinery or buildings could wait, but cattle never. They would be just as hungry on the 25th as any other day. Anticipating their needs was part of the routine of Christmas Eve, the first exciting part of the holiday itself. It was also the hardest working day of the year. The work of the 24th was nearly doubled, because to that day’s load was added everything that could be done in advance for the 25th.

The day began before breakfast: milk cows were tended—grumblingly by Stanton, lovingly if John was milking, mutinously by any of the boys. The barn was cleaned; horses were brought in, groomed, grained, and harnessed. After breakfast they were hitched to the 20-foot sleds. But before they could move, the runners had to be pried up from the ground, frozen solid by their weight each night. Four tons of loose hay were loaded and fed out on the snow; injured or ailing animals were treated; salt blocks and fences checked; water holes chopped open; and new feeding trails bulldozed.

Everyone knew no package would be opened on Christmas until every chore was finished outdoors, and until each household had its men back in.

My Christmas Eve was dedicated to trimming the tree—the belabored, long-awaited tree! Stanton was busy, so he assigned Fred. If tree raising had been on the ranch chore list, it would have been done quickly. Unfortunately, it was on the personal list—and houses and wives were well below cattle and machinery.

Some time later, Fred appeared, looked it over, and made the annual remark: “It won’t fit in the holder. I’ll have to get the axe.” An hour later: no Fred, no tree. A phone call to the barn: couldn’t someone, anyone, please get the damned tree up? “Certainly—don’t get excited, we’ll be right in.”

Meanwhile the younger children had unpacked every ornament, leaving them in chairs or all over the floor. Children from other houses drifted in, stepping on ornaments and comparing presents. Miraculously, each thought his own were the best.

Not only children came and went. We had spiced wine warming on the fire, so everyone found errands to do at our house. I even pleaded with bunkhouse boys: “Can’t you just quickly put the tree up for me?” “Sorry, Peggy, John’s waiting.”

Our hero this time was Harriet’s beau, a handsome, rather dim ranch hand from down the valley in new turquoise boots. He gazed solemnly at the tree: “It won’t fit in the holder. I’ll have to get an axe.” (That was my month to be rescued by axe-wielders.) He took forever, but the tree was so securely fastened the children could climb it—and did!

At long last we could trim. But where were my eager beavers? Off at another house, where the cookies were better. Even so, we didn’t lack for trimmers—nor confusion. Dave put one ornament on, Bill moved it, then Linc took it off to look at it. Evelyn loved every second ornament so much she begged to take it home for her tree.

The men drifted in and out for coffee or hot wine, bringing organization as they came. It never failed to amaze me that John could still get shocked surprise into his daily question: “Hasn’t anyone brought in the milk cows yet?

That night, supper was oyster stew—my idea that happy occasions could teach children to love new foods. The fresh oysters had been flown in, worth their weight in gold.

“Oyster stew!” said Dave. “I’ll have a peanut butter sandwich.”

“You can save mine for Santa,” from cynical Fred.

No matter. Made with our good ranch cream, the stew was an oyster lover’s dream. An oyster orgy. Not one was left for the turkey stuffing.

Christmas Eve in our family always meant presents still being made at midnight—the sewing bee around the fire, the workshop smelling of paint. This year was no different. Harriet’s beau even stayed to tidy, bless him—everywhere except the kitchen, of course.

Finally, I took one last look at our beautiful tree, then wished to each beloved one—as I wish to you—a Very, Very Happy Christmas.

And so, to bed.

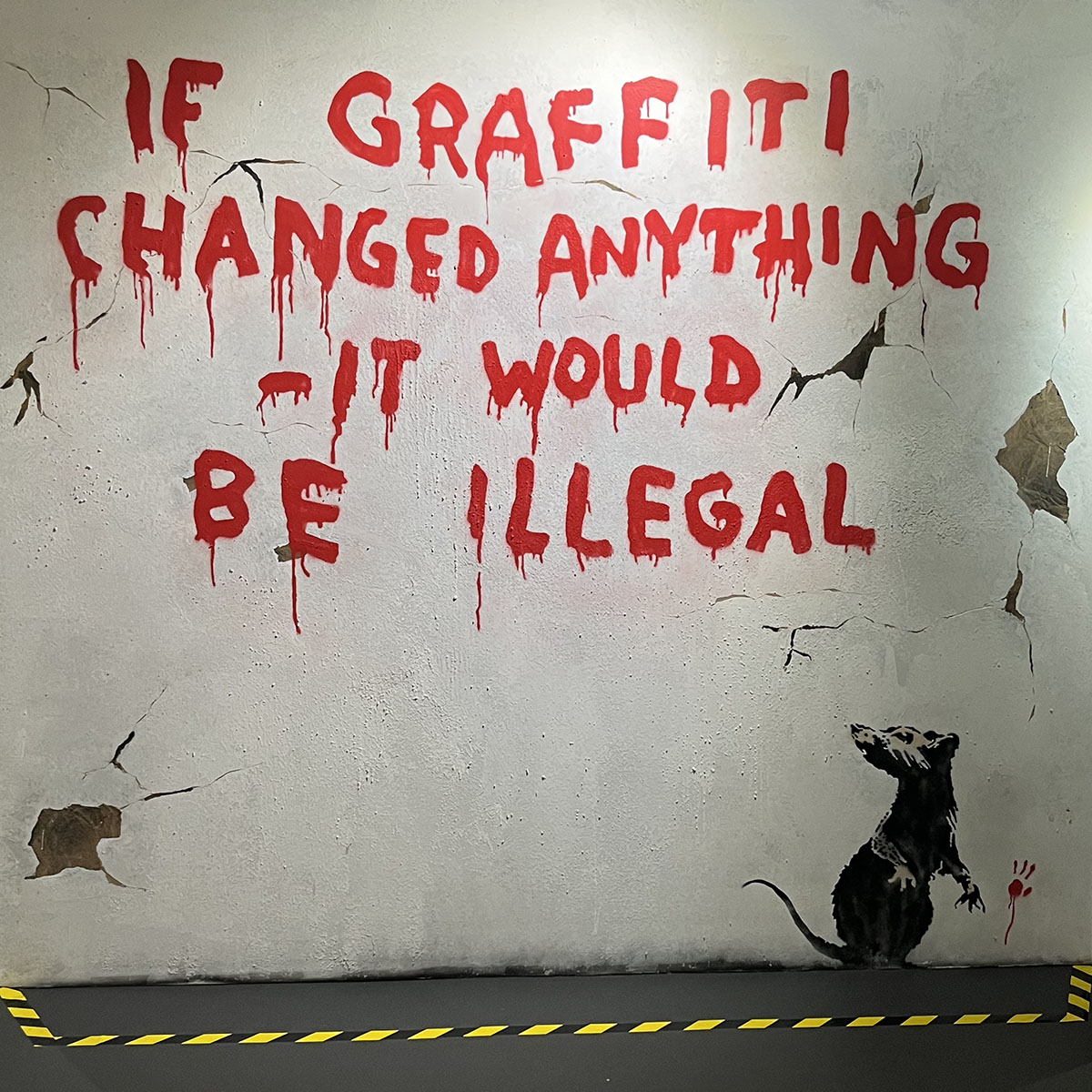

Elevate the Arts:Take the time to spend time with family and friends and remember to laugh at the challenges life throws your way. MF