A Ranching Community

by Thomas Yeomans, May 8, 1961

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2024 issue of Art with Altitude.

Its Life and its People: A Three Part Series

Part I—The Ranch Life

In the summer of 1959, I got a job working on a stock ranch near Steamboat Springs, Colorado. So when college ended, I threw my father’s old saddle in the back of the car, along with some other belongings, and started west. Though I had farmed some, this was my first contact with unadulterated rural life, and consequently, this summer had great effect on my life. As well as being enjoyable it showed me another way of life, another set of values that I had never experienced before, and I had to constantly test my own against them. Both the cowboys and I came off the wiser, having learned much about each other through days of working and resting together, united in one job, though from different backgrounds. The situation at the ranch was somewhat unique, for the boss and owner was an Easterner with a Harvard education, and the workers and their families represented varied rural backgrounds. We were all thrown together to work and live.

Steamboat Springs is located on the western slope of the Rocky Mountains, among what might be termed the “foothills.” Consequently, the terrain is mountainous with flat river-meadows between the ridges. The cattle are kept and fed on these meadows during the winter, and hay is harvested from them in the summer. The land is very fertile, for the snowfall is heavy during the winter, and it rains quite often during the summer months. Snow is on the mountains from October to June, and during the winter four to five feet will fall in the valleys. As I drove out to the ranch for the first time, I was overwhelmed by the greenness of the countryside. The road runs along one side of the valley, and one can look out across lush green meadows to the darker green foliage on the hills. The Elk River, bordered by tall trees, runs through the middle of the valley, carrying the melted snow down from the Continental Divide and supplying irrigation water for the meadows.

Though it is fertile country, the growing season is only 54 days, so everything is grown and harvested in the summer months between frosts. This means there is a great deal of work to be done in this short time, and less pressure during the cold months. The sun is quite hot during the day, but the heat is very dry, for the ranch is about 9,000 feet above sea level. It seldom rains for an extended period, but thundershowers, and occasionally hailstorms, are quite frequent during the summer months. Ranching is the main business in this area, either raising beef cattle, horses, dairy cattle or sheep. There is very little farming per se. Some mining still goes on, but it has declined in importance. There is no industry except possibly logging, which is carried out on a fairly large scale. Cattle-raising, then, is the main source of livelihood for these people. Consequently, the main crop is hay to feed the animals in the cold months. Little else is raised, for every bit of space is needed to grow enough to last the long winter.

Telephones have just recently been put in, and one or two radio stations can be picked up by the ranch radios. There is no television —this area is one of the last remaining places where television does not dominate people’s lives. The roads are all dirt, and in very bad repair. When it rains, they sometimes are a foot deep in mud. The mail comes once a day when the mailman can get through.

Generally speaking, this country is quite wild, and there are great tracts of wooded land, with no signs of civilization. The hills and mountains around abound in wild game, and the river and many mountain streams are well-stocked with fish. Deer particularly are plentiful, and there is a great influx of hunters during the season. This, in general then, is the area in which I was working and observing. It is a rugged place, demanding a rugged, outdoor life. It is a mountain environment, and through clearing and irrigation the ranchers have made it prosperous. But it remains a frontier, in a sense, for if you go farther west, you begin to come to the Easternized West coast. It is the “pure West,” if we may call it that, unspoiled by dude ranches and tourist attractions. Steamboat Springs caters somewhat to the tourists, but up the Elk River is this little pocket, and beyond is wilderness for fifty or sixty miles.

The ranch itself actually consisted of several ranches. The boss and his family lived at the main ranch. I was on an immediately adjoining ranch and worked there with the foreman, Howard, and the irrigator, Earle. This was very fortunate for me, for I got to know these men separately from the boss, John, and so found out what they thought of him. The ranch houses were set on the side of the valley, overlooking the meadows, and, though very simple in furnishings, they were quite comfortable. Each ranch had a barn and corrals, where the horses were kept and the cattle worked.

There was also a machine shop at each ranch, where even major repairs could be made, and tools of all sorts were available. Between the two ranches there were five tractors, a bulldozer, baler, and three trucks. Each place had its own gas pump and electric generator. From all this one might sense that the ranches were well-equipped, and indeed they were. This was because of the boss. We will learn much more about him later, but I can say here that he brought eastern efficiency and engineering skill to the business of ranching and spared no money on good equipment and ways to fix it.

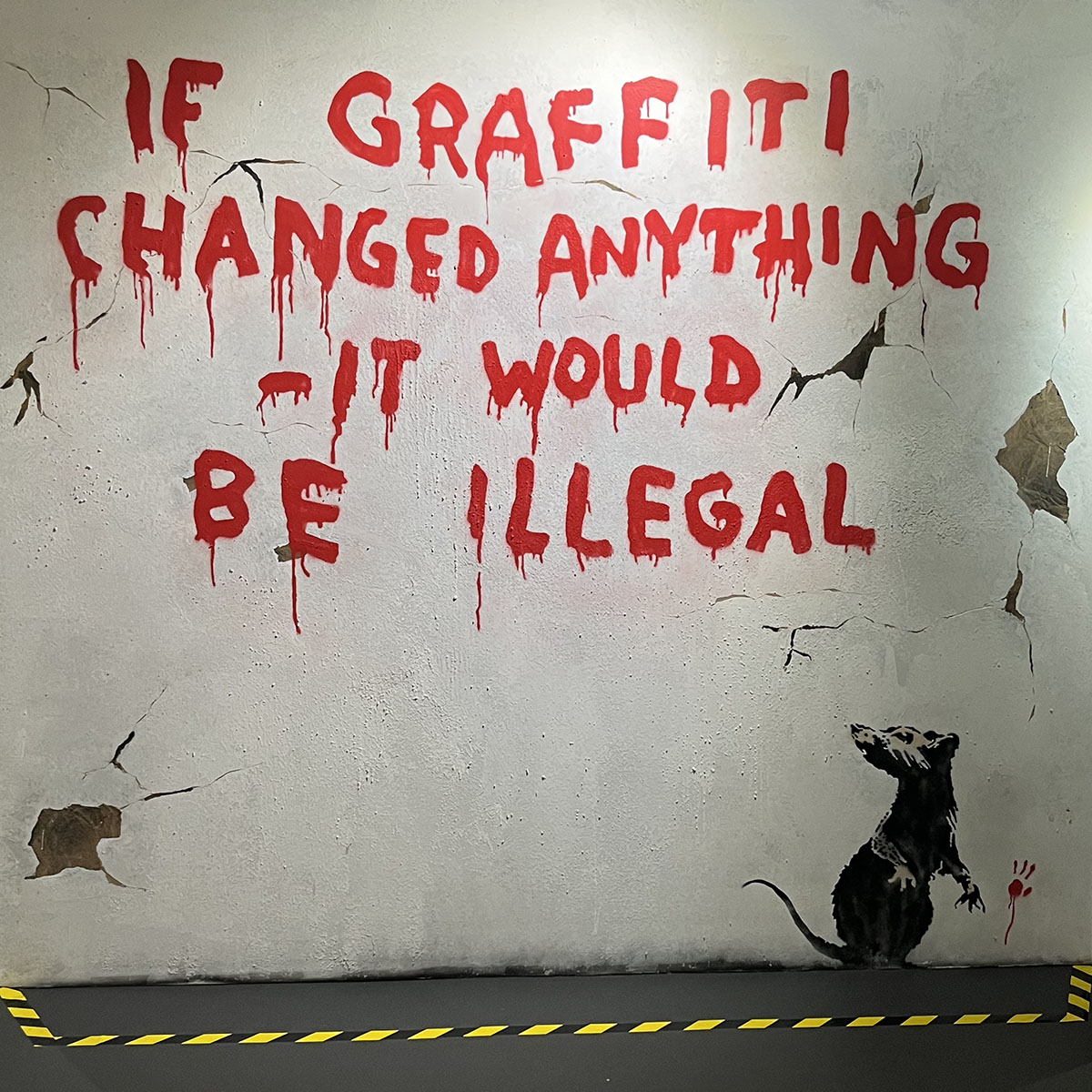

Practicality rules these people’s lives, both in thought and action. Music, the arts, philosophy, abstract thought, all means very little, and they would much rather be doing something than reading or thinking.

Family structure was another thing that struck me about this ranching community. The roles of the husband and wife are quite well-defined. The husband is master outdoors and does all the outdoor work. The women seldom come to the fields, except in an emergency when they may drive tractors to help get the hay in. But once the husband sets foot in the house, his lordship is over, and the wife rules the roost. She does all the cooking, serving, and clearing up afterwards. The men do nothing. For a while I used to jump up to clear the dishes and wash them, but I could see this was not appreciated by anyone. So, I soon stopped. The men are expected to obey orders in the house and stay out of the way. If they do not, they get in trouble. Each person has his absolute “sphere of influence” and these are very seldom transgressed.

Perhaps the thing that struck me most about this society was its openness, even taking into consideration its intolerance and suspicion of outsiders. When I arrived, they gave me a chance, took me on a venison roast and tried to make me feel at home. All were introduced by their first names, and they drew me into their talk. I felt very much alone at first, for everything was so new and different, but by the end of four days I felt I had a place among these people. There are many societies where it would take a long time to be accepted, but here, though I had to show I could work, I was soon taken in. Friendship means a lot to these people, partly because they are such a small and inter-dependent group, but also because they have a natural tendency toward it. Both their loves and hates are quite deep and unqualified. This was particularly true of Earle. As the summer progressed, we became closer and closer, and, as I have said, he was very fatherly toward me. One day when I was picking up bales and he was pulling the slip with the tractor, when we got to the stack, he unhooked and drove around the corner of the stack with the slip, and I thought he had gone. When I climbed the stack I saw him waiting in the field for me, beginning to load the slip himself, and when I ran up saying I thought he had gone off, he said, “Tom, I’ll never run out on you, don’t worry about that.” The way he said that left no doubt in my mind that he would gladly have given his life to save mine if the situation demanded it, and I felt the same way about him. I think that in another society you would not find such deep friendships spring up so quickly.

This, then, is the Fetcher ranch community, Steamboat Springs, Colorado. I have learned much from living in and studying a culture so vastly different from my Cantabrigian upbringing. TY